I have a longstanding debate going on with an accomplished Zen teacher and author about the ubiquity of trauma. All human infants, I maintain, experience trauma, and samsara is the inevitable result. In the best of cases, with secure loving attachments maintained continuously, the infant develops into an individual trapped in the Human Realm, his or her experience marked at every turn by the quotidian dukha (misery) and mild but pervasive tanha (striving) endemic to that mode of capture. My friend is not convinced I’m correct, but I’m encouraged by his interest in the questions I’m raising.

Why, according to my view, are we inevitably traumatized as infants? It is simply a function of our premature birth, and of the sensitivity of our nervous system to the inevitable affective shocks of birth and a long dependent infancy. We developed huge brains and, in order not to kill our mothers, we are born premature and endure a long, fraught dependency. Our huge brains are exquisitely sensitive and therefore easily marked by what we encounter in the world. Only recently, thanks to the work of neurologist Stephen Porges and others, do we understand some of the paradoxes of adaptation underlying our peculiar neurology.

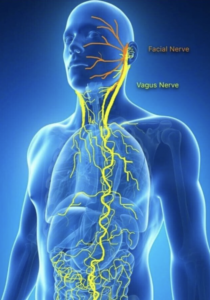

Evolution is a story of happenstance and workarounds, a kluge-operation of the first order. As it turns out, our development as social animals entailed an unfortunate recruitment of neural networks linked to primitive terror. The “fight or flight” circuitry of our reptilian brainstems needed to be “down-regulated” to include the possibility of social interaction, a feature of mammalian life in general and an adaptive step forward. In humans, of course, this development of social connection has reached exquisite refinement—the symphonic intricacy of the facial expressions and micro-expressions we routinely deploy to get along with each other, cooperating in complex ways. But this social capacity is rooted in the same neuronal circuitry that governs our “freeze” reaction when we find ourselves in mortal danger.

I’m talking here about the ventral and dorsal branches of the vagus nerve that emerges from our brainstems to branch out across our faces (the ventral vagus), while also traveling down into our guts (the dorsal vagus) to shut things down when we perceive the leaping tiger. This same dorsal vagus network gets triggered in the infant experiencing the terror of unmet needs that is a part of normal development. And unlike most mammals, we do not shake off this kind of shock, especially when it is iterative and pervasive, but remain in a dissociative state that becomes integrated into our development as autonomous individuals. The unfelt terror becomes a central thread in our developing ego such that we are haunted, to one degree or another, by trauma.

Another way to understand this is that the human infant inevitably seeks comfort in a precognitive conviction that the source of terror pertains to some flaw in his or her own nature. This as opposed to the far more threatening view that we are forever vulnerable to a world that does not always recognize our needs, much less address them. You could think of this as the “trauma turn,” a precognitive and milder version of how subjects of abuse often take refuge in being the source of the problem because it is more comforting to believe so.

I am no doctor, certainly no neurologist, and I’m hoping to hear where I have misconstrued the science here. But from the perspective of a dharma practice this view entails some major implications. Stated in the bluntest terms, every functioning ego is nothing other than a trauma structure. Born in the “trauma turn” mentioned above, the ego as a project is forever rooted in a dissociative response to primal terror, and the inner surface of this turn is the toxic affect of shame, lack, original sin. Call it what you will, it is rooted in what the Jungians call shadow – a source of intention and action we cannot take responsibility for because our very nature formed in order to ignore it.

Stephen Porges, Polyvagal Theory

The fact that every functioning ego is nothing other than a trauma structure helps explain why we are—each of us, right now—destroying the planet as a living system. As inconvenient as it may be, our normal, “civilized” functioning is deeply toxic to life. The normal functioning of an ego inevitably involves the shunting of negative, toxic emotions to the shadow where it does its toxic work. A committed dharma practice thereby becomes a long effort in the direction of a “true cost” accounting of the self, and the normative self-satisfaction of the Human Realm—where I am simply trying to be happy by drawing to myself the things I like and pushing away what I don’t like—reveals its pathological dimension. It is a form of life in the grip of death. No bueno. And the reason to embrace this desolate view is because doing so would allow us to address the growing problem of our own self-extinction.

Many dharma practitioners will recognize at least part of the truth of what I’m saying but shy away from endorsing it because it creates problems with the evangelical mission of Western dharma. We are at a crossroads, however, because Western dharma needs to integrate the healing practices linked to modern psychology—meditation is not enough.

On a more hopeful note, issues of systematicity come to the fore. We must ask ourselves how to distinguish systems of life from systems of dissociation and trauma. Our entire economy, rooted in abstractive, trauma-based dissociation—the culture of Wall Street and of capitalism per se—needs to be re-imagined as a system that promotes life, on balance, instead of death. We need to intervene in our social reward systems in a corresponding way so that the symbols and emblems of success are linked to life instead of death.

Phrased in this way the question becomes: what the hell are we waiting for?