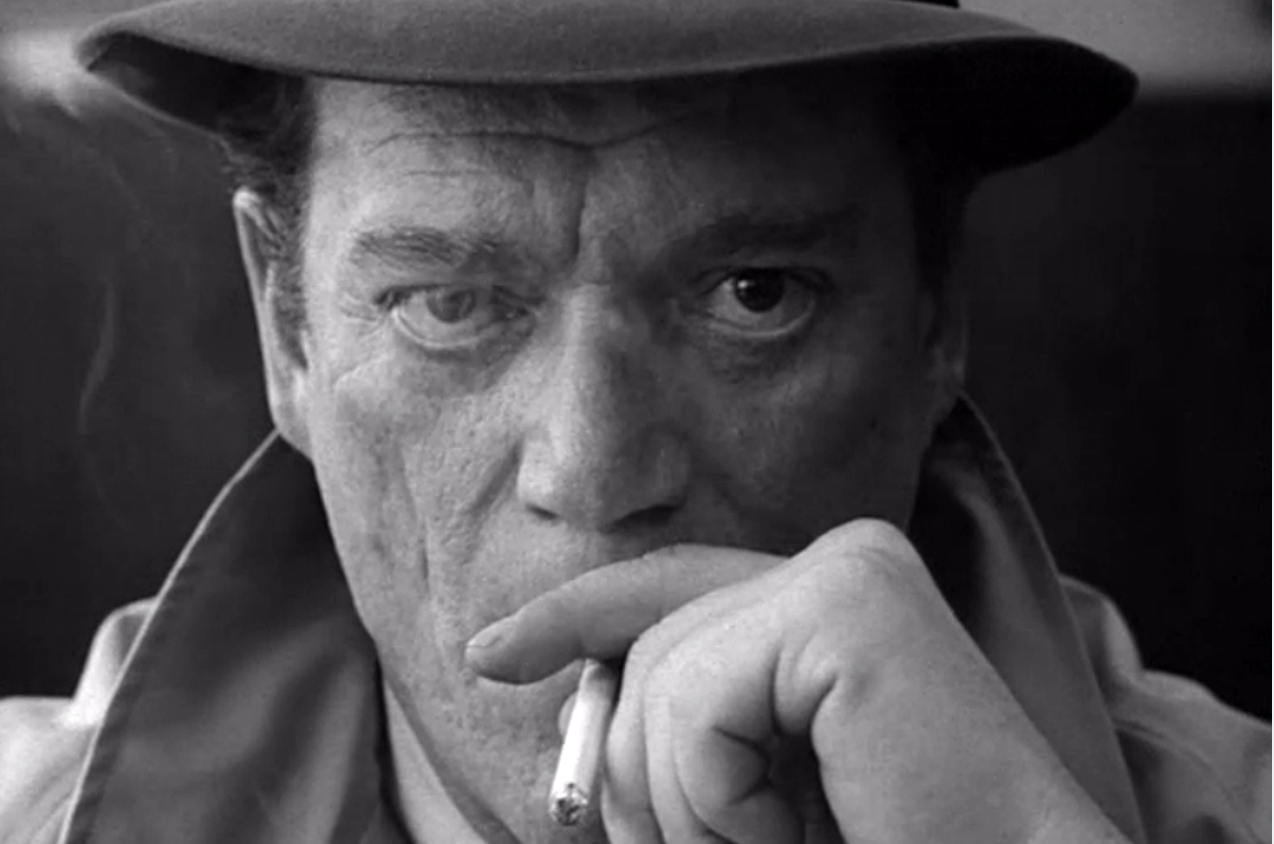

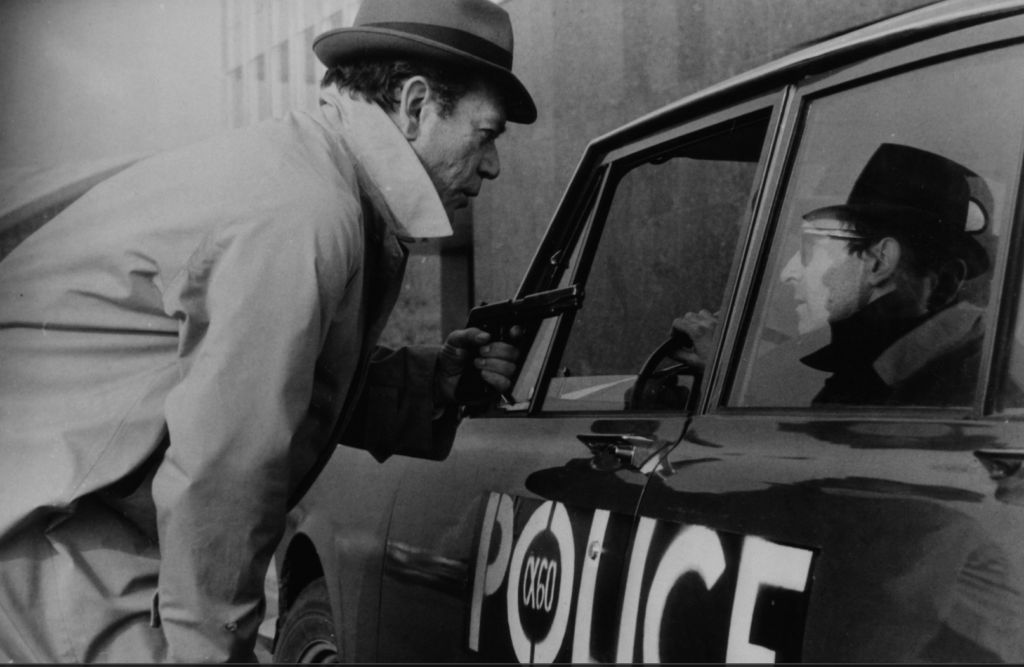

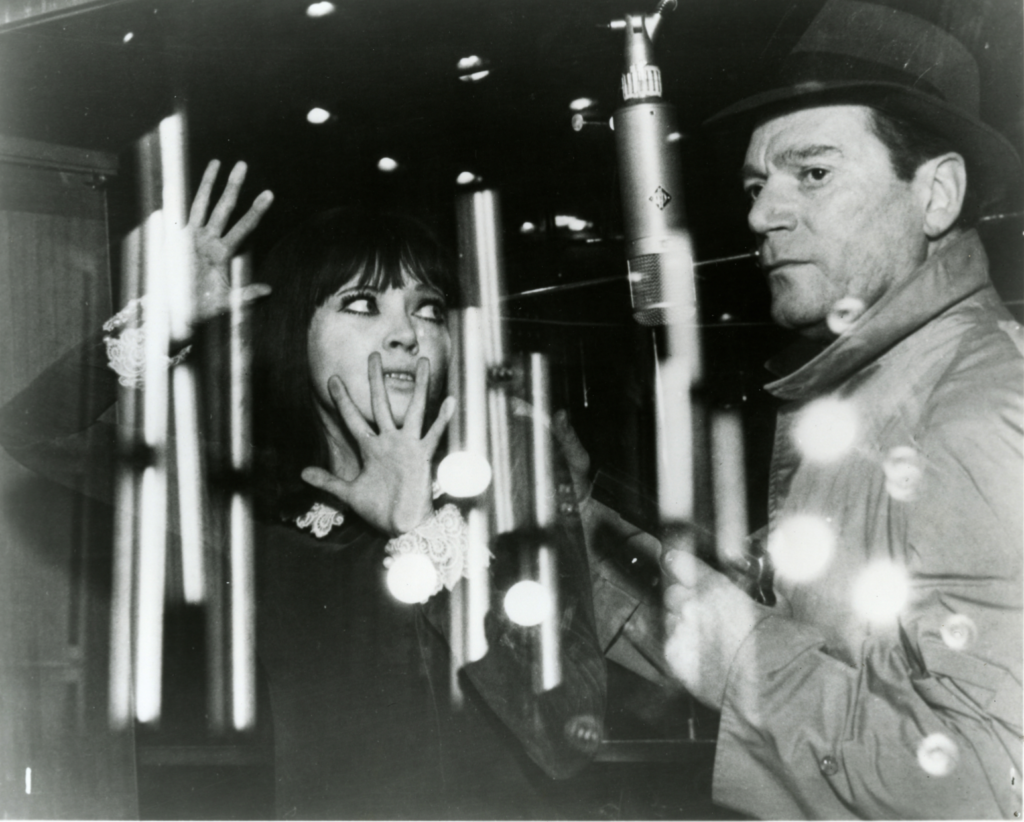

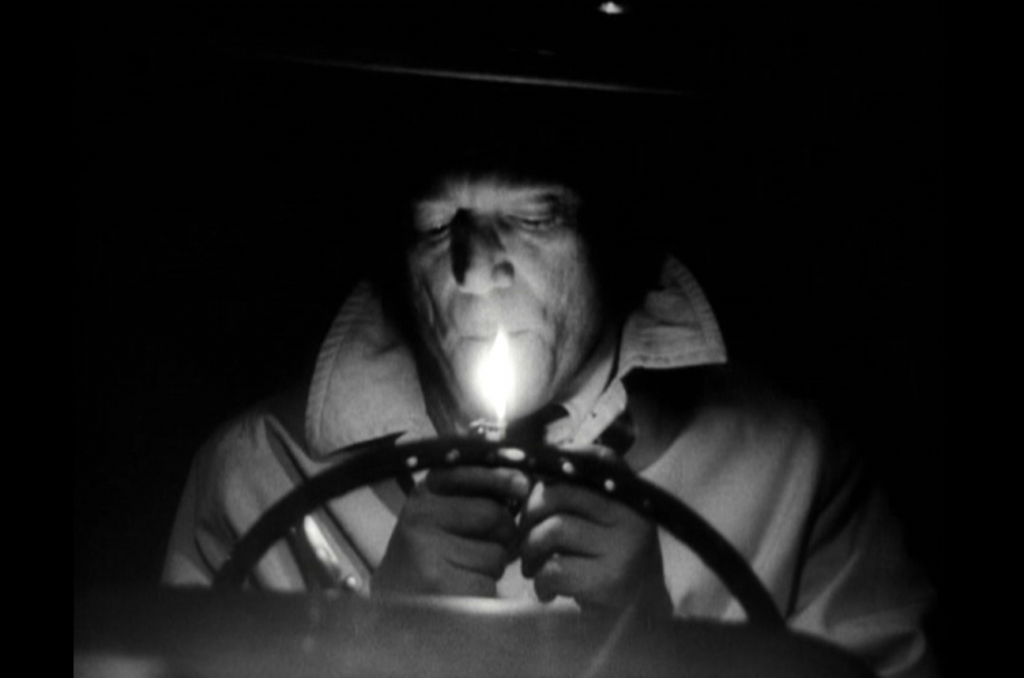

Re-screening early Godard films after his recent passing I am wonderstruck that we live in a world in which it is possible, at any time of day, and on any number of digital devices, to watch his 1965 sci-fi masterpiece Alphaville. Shot in black and white, the film stars the American jazz musician Eddie Constantine as Lemme Caution, an archetypal noir gumshoe in a fedora and a trench coat. Alongside Constantine, the film features Anna Karina (who Godard was then married to), and the great character actor Akim Tamiroff, along with a host of extras.

The plot of Alphaville is simple enough. Lemme Caution arrives in Alphaville licensed to kill. A city devoid of art or poetry, logic rules Alphaville to such a degree that nobody in the city uses the word why anymore, all they say is because. In control of every detail of this nightmare world is a sentient computer named Alpha 60.

Lemme has been sent to kill Herbert von Braun, Alpha 60’s creator. Soon after Lemme arrives, Von Braun’s beautiful daughter, Natacha, knocks on his door. Dispatched on a mission to distract Lemme by seducing him, Natacha instead falls under the spell of his implacable cool. She soon becomes Lemme’s guide and protector and together they navigate the labyrinth of Alphaville to pull the plug on Alpha 60. As day breaks, Lemme departs with Natacha in his Ford Galaxy, having enforced justice in a future that was behind us even back when the film was made.

One of the themes of this blog is how trauma sets up a system within us composed of all the things we carry forward because they were too painful and confusing to experience. Those first upsetting encounters with the vast, chaotic, ever-changing world, experienced as a cortical, adrenilated terror, go directly into the tissues of our bodies. There they protect and constrain us, armor-like, as we set about enacting our various fates.

While systems are loaded with dynamics and energy, they have zero awareness and are devoid of life. When we say living systems, for example, we mean a collection of living entities organized systemically—all the life is elsewhere from the systemic quality. Trauma, therefore, delivers our vital energies to dynamics that are devoid of life, and that is dangerous.

How do you know when you’re caught up in a system? One sign is that, to quote Lemme, “you never hear why, all you hear is because.” Amplifying the danger of our current cultural mode is that those who are most active and empowered addressing our various problems are engineers and businessmen, social types defined by a love of because-thinking. They are, right now, making steady advances, despite loud warnings and alarms, toward machine-learning and artificial intelligence, thereby delivering us to the dynamics mentioned above, dynamics devoid of life or awareness. The noir hero, by contrast, is the being who enacts why in the mode of action by solving a crime. All signs point to how we need another visit from Lemme Caution.

With films by Godard, for me, the moment of aesthetic bliss happens early—a kind of awestruck gratitude arriving five minutes in. Godard is the kind of director you form a kind of school-girl crush on—he’s so aloof, that sexy Jean-Luc…! Alphaville is lit up with the an ecstatic, postwar-American joy: fast cars and fedoras, doomed masculinity, certain iconic cuts and camera moves, and the sound shoe leather makes on marble or concrete. A noir classic, Alphaville seems today quite prophetic in how it has linked the dissociative power of the tyrant to the growing threat of the big because-machine called AI.

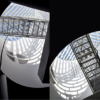

Among the film’s brilliant touches is how Alpha 60, appearing visually only as a light that blinks on and off the computer itself, speaks directly to us in a striking cancer-ward voiceover:

Time is a river which carries me along, but I am time.

It is a tiger, tearing me apart, but I am the tiger.

Time is like a circle which turns endlessly.

The descending arc is the past, the arc that climbs is the future.

By giving Alpha 60 a poet’s sensibility, Godard is being generous to the humanity of tyrants, those who enact the fiction that we live in a world where all problems can be solved. The poeticism of Alpha 60—much of the text was taken from Jorge Luis Borges—only highlights the horror of its utter commitment to the logic. Alpha 60 deprives the citizens of Alphaville of the dreams it savors most.

Those who are busily constructing AI embrace a Kantian model for how intelligence functions that goes by the name predictive processing. Developed over the past decade by thinkers such as Andy Clark and Carl Friston, everything in predictive processing is upside down and backwards from what we typically assume. Our brains do not simply take in sense data and then organize data into a coherent world. Rather, our brains construct predictive models and then attend to the sense gates to see what the model gets wrong. We then turn the knobs of this generative model, adjusting our internal simulation to minimize the prediction errors between the model and our sensory data. Restraining the huge number of possible models by utilizing certain presuppositions or “priors,” the brain seeks to minimize prediction errors. We seek not just the best fit model, in other words, but the best fit model as close as possible to our prior expectations. What is radical and new about this theory is the notion that most of what we experience moment by moment is simply the predictive model and its deviations, not direct experience.

As Lemme knows, this is not just a story of the mind, of cognition and computation. The feeling body is also inscribed, along with the brain, by unprocessed experience—the priors of trauma, one might say. In the end, therefore, the reign of the computational mind can be nothing but tyranny.

In his films Godard was always intent on relating to the cinematic as a separate category of aesthetic experience, and this makes Alphaville, like many Godard films, simultaneously more than and less than a movie. And yet, problematic as they may be as entertainment propositions, Godard’s films are works of art—they’re not the same, you know, art and entertainment. In their ironic stance toward dramatic representation, Godard’s films never wants us to forget that we are watching a movie. In this commitment to irony, Godard’s body of work can maybe be viewed as the high-water mark of Bertolt Brecht’s impact on cultural expression. In Alphaville, Brecht’s wariness of narrative meshes perfectly with Godard’s love of noir style and the cultural energy of postwar America.

About Godard’s films my inner critic notes that irony is a difficult mode to sustain past a certain duration. By the fifty-minute mark of a film by Godard the aesthetic bliss is troubled by a growing recognition that the emotional connection I am waiting for will never arrive. Something leaves the experience then, my feeling critic says, Godard’s ironic remove taking back with one hand what he just gave me with the other. Alphaville, I want to say, is perhaps not a film so much as the memory of a film, the way an aphorism is the memory of wisdom.

Lemme is having none of it.

“Whether you like Alphaville or not is irrelevant!” he shouts, slapping me hard across the face. “Either way you gotta deal with me,” comes the backhand. Slamming the door on his way out, Lemme leaves me strapped to that chair–the film’s themes are deeply resonant with our time. The world of Alphaville is also the world of AI we will soon inhabit.